There is a story about the emperor Napoleon once asking the scientist Laplace why his new book did not mention God.

Laplace replied, “I had no need of that hypothesis.”

Whether or not Laplace actually said it, his attitude is shared by many scientists today. In 2009, a Pew research study showed that scientists are ten times as likely as the general population to disbelieve in God or even a “higher power.”

Significantly, the same study showed that many scientists still believe in God (33%), and still others believe at least in a universal spirit or higher power (18%). That means over 51% of scientists believe in a transcendent being or power.

From a scientist’s point of view, what evidence might there be to support belief in God?

In this post, we’ll summarize the best, current scientific evidence for God and provide you with plenty of links if you want to dig deeper into the specifics. We’ll also offer a free download of a chapter from Fr. Spitzer's book, The Soul's Upward Yearning. This chapter will answer questions such as "Has science disproved the existence of a creator?" and "Can science give any evidence for a transcendent creator?" Access your free download below.

Table of Contents

When We Say "Scientific Evidence for God," What Do We Mean Exactly?

Generally, a “hypothesis” is a possible explanation for something we observe. In strictly scientific terms, however, a hypothesis must also be testable. If you can’t run an experiment to prove or disprove the hypothesis, then as far as scientists are concerned, it’s not a hypothesis.

There are, for better or worse, no scientific experiments that prove or disprove the existence of God. Scientific experiments must be conducted on the natural, physical world around us. God, if he exists, is supernatural and transphysical: not part of the physical world in front of us.

If there can’t be a scientific experiment to prove God’s existence, how can scientific evidence exist for God?

As it turns out, you can have evidence for something even if you don’t have an experiment for it.

For example, imagine someone asking you, “Do you believe that I love you?” You might believe them, or you might not. Either way, your belief would not depend on an experiment that proved that the person loved you. Your belief would depend, however, on your observations of that person, which would serve as evidence of whether or not you should believe that person.

In the same way, while science may not be able to design an experiment to prove God's existence, it can provide numerous observations that point to His existence.

In this post, we’ll look at two groups of observations:

- Evidence that the universe had a beginning

- Evidence that the universe is fine-tuned.

Did the Universe Have a Beginning, and Is That Scientific Evidence for God?

To understand this line of evidence, let’s suppose that science indicates the universe had a beginning. How would that be evidence for God?

An ancient philosophical principle states that nothing comes from nothing. If the universe had a beginning, then it had to come from something; otherwise, it would have come from nothing, which is impossible.

Ex nihilo nihil fit (nothing comes from nothing). —Philosophical principle first argued by Parmenides

Furthermore, if the universe had a beginning, it had to come from something other than itself. Self-evidently, the universe itself couldn't have existed before its own beginning. Something else must have.

The universe, remember, is the sum total of all-natural, physical things. Thus, the “something else” that existed before the universe could not have been a natural, physical thing. It would be part of the universe, not separate from it if it had been such a thing.

Thus, if the universe had a beginning, it had to come from a supernatural, transphysical being.

Consequently, if science indicates that the universe had a beginning, then that is powerful evidence for a supernatural, transphysical being that created the universe. In other words, that is powerful evidence for God.

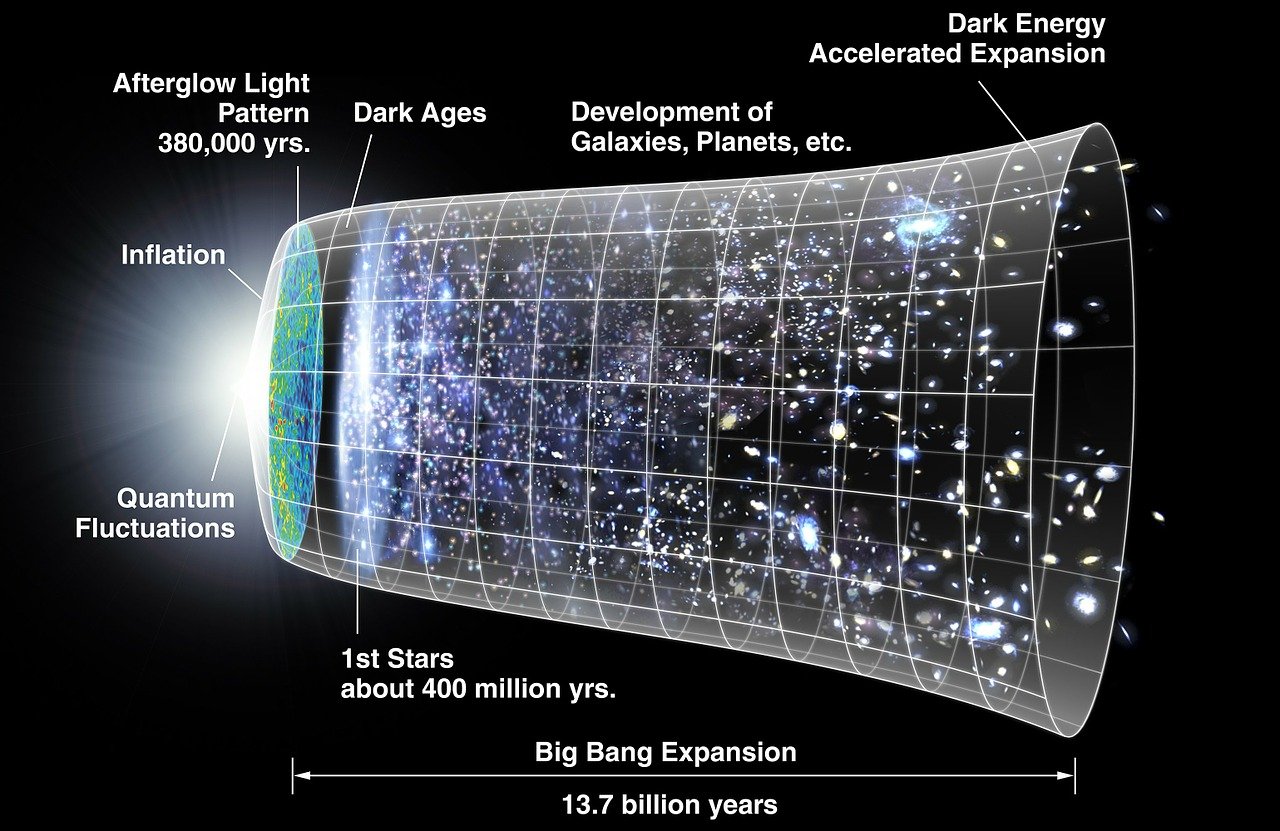

But does science, in fact, indicate that the universe had a beginning? The Standard Model states that the observable universe suddenly expanded from a small singularity around 13.8 billion years ago—an event known as “The Big Bang.” But there’s little more than speculation about what kind of physical existence there might have been before the Big Bang.

The timeline of the universe begins with the Big Bang. / NASA/WMAP Science Team / Public domain

The timeline of the universe begins with the Big Bang. / NASA/WMAP Science Team / Public domain

Despite the limit that the Big Bang places on our knowledge, science can provide two strong arguments for why physical existence had to have a beginning. The first is called the Borde-Vilenkin-Guth Proof, and the second is evidence from entropy.

Scientific Evidence for a Beginning: the Borde-Vilenkin-Guth Proof

To understand the Borde-Vilenkin-Guth (BVG) proof, we must start with the Hubble-Lemaitre Law. This law states that galaxies are moving away from Earth (our observation point) at speeds proportional to their distance. The further away they are from us, the faster we observe them moving away.

The "Hubble-Lemaître" law describes the speed at which objects move in an expanding universe.

The standard scientific explanation for this is that space is expanding. Consequently, the more space there is between us and another galaxy, the more expansion there will be. Hence, from our perspective, the galaxies' velocities grow greater over time.

Imagine that you could hop in a spaceship and head toward one of these other galaxies at 100,000 mph. Since the galaxy is moving away from you, your velocity relative to that galaxy will be lower than 100,000 mph. If the galaxy is moving away at 20,000 mph, for example, then your velocity relative to it will be 80,000 mph.

Bearing that point in mind, we come to the beginning of the BVG proof. Since galaxies are moving away from us faster and faster over time, the relative velocities of objects moving toward them would slow down over time. Thus, the relative velocities of such objects must have been faster in the past.

At some finite point in the past, relative velocities would have reached the speed of light. Scientists generally agree that the speed of light is the maximum possible speed. Thus, this point would have to mark the beginning of time and the universe as we know it. Even if it turns out that there is a velocity greater than the speed of light, that will not undermine the theory—it only states that there is a “maximum velocity.”

Suppose, however, that a higher velocity than the speed of light was discovered in our universe. The Borde-Vilenkin-Guth proof would not be undermined. For the BVG proof, it does not matter what the highest velocity is, but only that there must be a maximum velocity (whatever it may be). The past velocities would eventually reach it as long as there was a maximum velocity.

Moreover, there must always be a maximum possible velocity in any universe or multiverse. To understand why, you should imagine that physical energy could have an infinite velocity. If its velocity were infinite, it would be everywhere at once. This would create a problem of multiple manifestations of energy and a series of intrinsic contradictions.

Thus, there must be a beginning of every universe or multiverse with an average rate of expansion greater than zero—such as our universe, which has been expanding ever since the Big Bang.

For more on this, see the video below:

Scientific Evidence for a Beginning: Entropy

The second line of scientific evidence for a beginning comes from entropy.

To understand this evidence, one must understand that physical systems tend to move from disequilibrium to equilibrium. For example, there’s a difference in temperature between an ice cube and a glass of water. When you put the ice cube in the glass of water, it melts and cools the water. The physical system ends up with the same amount of energy but more evenly distributed, i.e., in equilibrium.

When a physical system’s energy moves, it loses some of its disequilibrium overall. The ice cube can’t melt again; it’s already melted. You can refreeze the water in the glass, but to do that requires putting energy into your freezer: the overall system still tends to equilibrium.

Over time, the universe necessarily moves from disequilibrium to equilibrium. Statistically, it has to.

If the universe had always existed, it would be at maximum equilibrium today; all energy would be evenly spread out throughout it. No movement or work, in the scientific sense, would be possible.

The universe, however, is not in such a state; therefore, it cannot always have existed. And since the universe exists now but didn’t always exist, it must have had a beginning.

For more on entropy and if it can indicate the beginning of the universe, watch the video below taken from Fr. Spitzer’s 12-part series “God and Modern Physics.”

These two pieces of scientific evidence—the Borde-Vilenkin-Guth proof and the evidence from entropy—make it clear that the universe had a beginning. Taken together with the principle that “nothing comes from nothing,” they are strong evidence that the universe originated from a supernatural, transphysical being separate from it. In other words, they are strong scientific evidence for God.

Scientific Evidence for Fine-tuning: Further Evidence for God

Certain conditions are necessary for any complex life form to arise in a universe. When scientists examine these conditions, they agree that they are exceedingly improbable. Since these conditions are extremely improbable, scientists are left with two possible explanations.

The first explanation is supernatural design.

The second explanation is that our universe is one of unthinkably many. Conditions within these universes would need to vary randomly. If there were enough of them, then it would be likely for a universe such as ours to exist.

Before deciding which explanation is more likely, we should examine some of the conditions that make our universe so improbable.

What Fine-tuning Examples Might Be Evidence for God?

You can follow this link for a more in-depth explanation of different fine-tuning examples, but the following is a summary of the most important examples.

- In order for life to develop, the universe needs to start with very low entropy. Mathematical Physicist Roger Penrose calculated that the odds of our universe starting with such low entropy purely by chance were 1 out of 10^10^23 (see the video below for more on this).

- In order for life to develop, it needs habitable planets. Physicist Paul Davies has determined, however, that if the gravitational constant or the weak force constant were different by 1 in 10^50, the universe would either have expanded or collapsed catastrophically. Galaxies would not have formed, let alone stars or habitable planets.

- Similarly, slight differences in the nuclear force constant would cause either no hydrogen or only hydrogen. Either way, a complex life would not have been possible to develop.

- Slight changes in either the gravitational or fine structure constant would have resulted in all stars being red dwarfs or blue giants. Neither kind of star is suitable for life.

Is This Scientific Evidence for God or for the Multiverse?

We’ve examined two lines of scientific evidence for God. One indicates the beginning of the universe, and the other indicates that it is fine-tuned.

We’ve suggested that both these sets of evidence indicate the existence of a supernatural, transphysical creator. But what if they instead were evidence for a multiverse?

According to the multiverse explanation, our “universe” is only one of many. Our individual universe may have had a beginning—likely the Big Bang—but the multiverse may be eternally churning out bubble universes for all we know. Therefore, if there are trillions of “universes” within the multiverse, then it is unsurprising that one so fine-tuned as ours could arise by chance.

The multiverse theory is currently the strongest alternative to supernatural design, but it has several weaknesses:

- By definition, the multiverse and all the other “universes” would be unobservable. Consequently, the multiverse is not a scientifically testable idea. No observation you make would prove or disprove the multiverse.

- The principle known as Ockham’s Razor states that all things being equal, simple explanations are preferable to complicated ones. The multiverse is a very complicated explanation, requiring trillions of bubble universes—and some sort of system for generating more!

- Furthermore, should the multiverse exist, it would still require a beginning. The multiverse would have to be inflationary since it’s supposed to be busily churning out more universes. It also would have to have a finite, maximum possible velocity— otherwise, energy could have an infinite velocity and would be everywhere at once. Thus, the multiverse would also be subject to the Borde-Vilenkin-Guth proof and would still require a beginning.

- Finally, all current theories of the multiverse require very specific conditions in order to work. This places them, once again within the realm of fine-tuning.

Thus, besides being questionable, multiverse theories don’t suffice to explain away the beginning of reality or the fine-tuning present within it.

As such, these theories should not prevent the scientific evidence for God from being accepted. Whether or not reality began during the Big Bang, it still needed to have a beginning. Whether or not there are many other universes, reality needs to be finely tuned to function as it does. God may not be a scientific hypothesis, but given the current state of science, the evidence certainly suggests that God exists.

For more on the universe's beginning and if science can give evidence for a transcendent creator, download your free chapter from Fr. Spitzer's book, The Soul's Upward Yearning, below.

*Originally published on October 25, 2020.