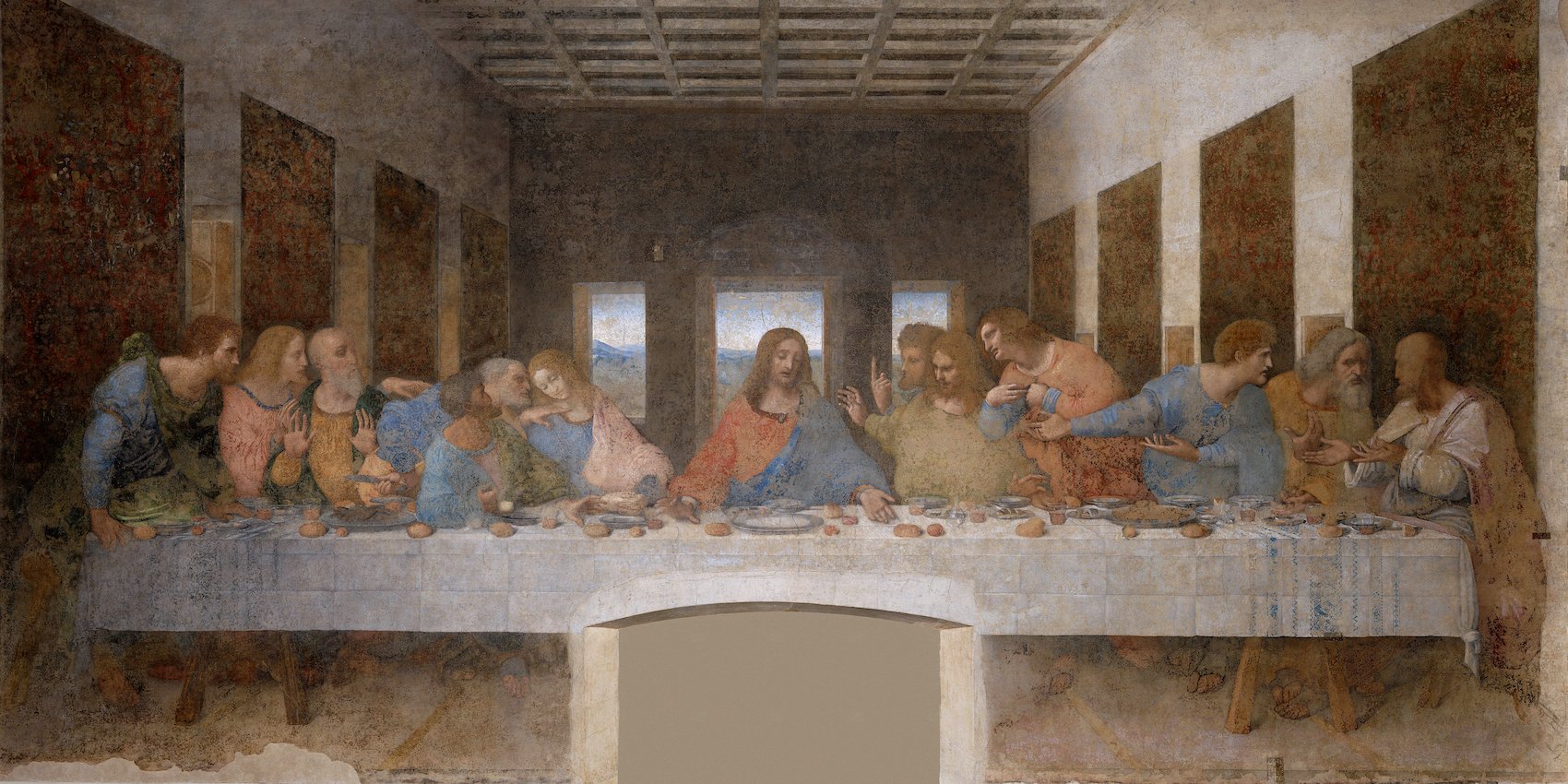

Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, located in a ruined monastery in Milan, is one of the most iconic paintings in the world. It has inspired countless imitations, spoofs, and reimaginings, and it remains one of the most recognizable works of art in all of history. Its fame endures despite both huge cultural shifts away from traditional religion and the lamentable condition of the artwork itself, which started to fade almost immediately after da Vinci completed it.

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci / Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci / Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

So. . . Why Is the Last Supper So Famous?

Is it famous simply because it’s by Leonardo da Vinci, the quintessential “Renaissance man?” Well, that’s surely part of it. Leonardo’s genius, of course, is legendary, embracing biology, geology, engineering, mathematics, and art. But that’s not a full explanation. Leonardo, after all, made other, lesser-known things that are in much better condition and are much more accessible to tourists, such as his Madonna of the Rocks, whose two versions reside in London’s National Gallery and the Louvre.

Virgin of the Rocks (sometimes referred to as Madonna of the Rocks) by Leonardo da Vinci / Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Virgin of the Rocks (sometimes referred to as Madonna of the Rocks) by Leonardo da Vinci / Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Or maybe, more than da Vinci’s lesser-known works, the Last Supper has coasted on the Mona Lisa's fame, reminding viewers of that mysterious, hard-to-read heroine. Indeed, historical records suggest that da Vinci deliberately made the Jesus of his Last Supper elusive and sphinx-like, with a hazy expression that defies description. But this explanation, too, isn’t quite sufficient. We tend to forget, for example, that the Mona Lisa was relatively unknown until 1911 when it was stolen from the Louvre by a disgruntled Italian nationalist. The fame of the Last Supper far outshone that of the Mona Lisa until recently!

Or maybe the Last Supper is famous just because it’s famous. Maybe, simply by historical accident, it was copied a lot and widely seen—sort of like the Renaissance equivalent of a catchy jingle or an annoyingly omnipresent advertisement. But this prompts the question: what made it “catchy” in the first place?

Imitation of Da Vinci's the Last Supper by Giampietrino, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Imitation of Da Vinci's the Last Supper by Giampietrino, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The long-standing popularity of da Vinci’s Last Supper, it seems, points to something intrinsic to the picture itself—something elemental that da Vinci captured. What is it?

Da Vinci’s Last Supper: An Icon of Human Community

I think what da Vinci captured, in its most distilled and timeless form, was human community—human community as no one else before had managed to crystallize it. The “community” of da Vinci’s Last Supper, as we can see, is not merely physical togetherness. It is a rather shared, conflicted, interconnected response to an elusive Central Good.

Popular expressions like “a seat at the table” and “breaking bread together” get parts of the meaning of da Vinci’s painting. A common meal has long been a symbol of inclusivity, intimacy, and shared life. But da Vinci’s work transcends those expressions. There are so many stacked, complementary layers, hinting at the difficulties of collaboration, the strength of affectionate bonds, and the frictions of different personalities. These layers become possible when the “Central Good” is also a Person whom one can see and touch.

Thus, there is the inclusivity of the shared table. There is the intimacy of the communal dish and loaf. But there is also the stubborn uniqueness of all the disciples. In answer to Judas’s betrayal, there is the chaos of conflicting emotions: sadness, shock, indignance, secrecy, and resignation. And in the figures’ body language, there are powerful social signals of inside and outside, high and low, and near and far, implying favor, rank, and degrees of fidelity.

And amidst it all, there is the reassuring weight of the stable Center: the pyramid-shaped Jesus, extending his hands with grave serenity. This a quiet, radiant Center unperturbed by the unfolding, messy complexity of clashing personalities and secret enmities. Around it—around Him—every figure is joined in a rhythm that flows like water and swirls like the wind.

Around Jesus, the eye, there circles our human “storm.”

And that is not all: for Da Vinci has situated this micro-community—this archetypal stand-in for every human society that has ever haltingly sought the Good—within a space of such sleek generality and mathematical elegance that it could be almost any place, in almost any era. Unlike earlier artists who painted the Last Supper within marbled halls or columned porticos, anchoring them in history, da Vinci’s Last Supper is cosmic. It is fixed in the metaphorical skies of the human imagination like a constellation, faintly glowing and never changing, with a reassuring familiarity that reaches into the depths of time.

Mary Beth Edelson, Salvador Dali, and the Last Supper

It is no wonder, then, that Salvador Dali replicated da Vinci’s Last Supper in his own surreal, almost sci-fi idiom in 1955. Here, Jesus and his disciples seem to be in a spaceship, sharing a ritual meal in some distant, almost transhuman future. Somehow, Dali’s take feels appropriate. There is something futuristic about the Last Supper—both da Vinci’s version and the institution itself. Jesus did command, after all, that the event should be re-enacted again and again until the end of all things. Furthermore, Catholics believe that Jesus himself offers the Mass's sacrifice through the priest's mediation in manifold acts of timeless, superhuman, omnipresent succession-in-simultaneity. (This helps explain the floating spirit-body in Dali’s version.) And Jesus will continue to do this, Catholics believe, a hundred years from now, or a hundred thousand, if the world still turns.

Dalí, Salvador. The Sacrament of the Last Supper. 1955. Oil on Canvas. Permission granted by the National Gallery of Art.

Dalí, Salvador. The Sacrament of the Last Supper. 1955. Oil on Canvas. Permission granted by the National Gallery of Art.

It’s no wonder also, therefore, that the feminist artist Mary Beth Edelson chose da Vinci’s Last Supper to make a statement about woman artists in 1972. Here, Edelson replaced Jesus’s features with the face of the artist Georgia O’Keeffe and overlaid the disciples’ faces with those of other woman artists. The result swings between humor and sacrilege, but the vividness of the message is never in doubt. Only an inspiration as powerful and iconic as da Vinci’s Last Supper could raise issues of gender, inclusion, exclusion, hierarchy, and value so clearly and instantaneously.

Can Art Have Universal Resonance?

At my university, my students and I debate whether works of art or the values of art movements could possibly have universal, global resonance. Is such a thing even possible? Or are the cultural divides of human communities ultimately too deep to cross? Is there a common humanity that unites us, enabling us to come together around shared truths and experiences, or is “humanity” a fiction overlaid on a fluid, evolving phenomenon that is never really the same from one day to the next or from place to place?

I believe some things—the great works of art among them—tap into something universal and elemental. These things sometimes seem faintly outlined in light, as if they at once hide and reveal, eclipse-like, a higher truth, a shared “sun” that all of us instinctively know is there. Thus, we grasp for words like “great” or “iconic” when we speak of them. We obsess, contemplate, spill words, and travel distances to study these things, to interrogate them. Though in real life, they may fade into shadow (like da Vinci’s crumbling fresco), they throb brightly in the imagination of those who have seen them, speaking eternally of truths that seem to transcend time and space.