In order to track a Luciferian serial killer, Robert Downey, Jr’s film-version of world-famous master sleuth Sherlock Holmes singly enters into a satanic ritual in the first installment of the Sherlock Holmes movie franchise. While it is repugnant, ill-advised, arrogant, and reveals typical ignorance of playing around with things demonic, the fictional character makes an obvious point: one can enter into a person's mind and figure out his intentions and mental habits by entering into the rituals that he regularly practices.

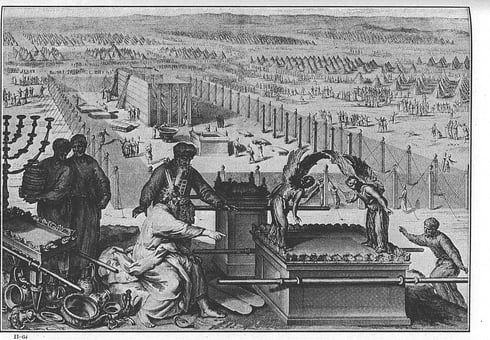

Once God revealed himself on Mount Sinai, and once Moses instituted that pattern in the Tabernacle and in the priesthood, then all previous narratives received a final form and were purified of all previous misconceptions. The Tabernacle itself gave a purified cosmology and understanding of creation, while the furnishings inside the temple and the Levitical priesthood established a sacramental worldview and expectation of a future Messiah. AB/Wikipedia

Once God revealed himself on Mount Sinai, and once Moses instituted that pattern in the Tabernacle and in the priesthood, then all previous narratives received a final form and were purified of all previous misconceptions. The Tabernacle itself gave a purified cosmology and understanding of creation, while the furnishings inside the temple and the Levitical priesthood established a sacramental worldview and expectation of a future Messiah. AB/Wikipedia

While an Enlightenment character like Holmes may see himself as above religious ritual—and even see the religious practice as pre-scientific—he still sees the value of understanding cults to understand a person's mindset and community. This essay defines “cult” as a religious ritual or practice with no intrinsic negative connotation. Cult is simply what provides context and insight to understand the way a practitioner or protagonist views the world and interactions between God and man or between man and spirits.

Mount Sinai: Entering the Cult to Enter the Mind of the Author

Before modern secularist political movements emptied culture of appeals to higher but unseen spiritual realities, the religious cult defined culture and therefore shaped a person’s worldview. Not only did the religious cult profoundly and daily affect home and hearth, but the cult also gave context and reference to legends (both local and national). If one wishes to enter an ancient author’s cultural and historical mindset, if one wishes to understand the author’s context and audience, then knowing his cult—his ritual practices—becomes even more relevant to identify when he is applying such cult—as practiced in his day—to ancient legends of mankind’s origins and similar theological narratives. For instance, is the cult established at Mount Sinai applied to narratives of Eden when Moses gives the Torah?

For proper exegesis of Sacred Scripture, the authentic tradition and voice of Scripture’s guardian are clear:

“The interpreter [of Scripture] must investigate what meaning the sacred writer intended to express and actually expressed in particular circumstances by using contemporary literary forms in accordance with the situation of his own time and culture. For the correct understanding of what the sacred author wanted to assert, due attention must be paid to the customary and characteristic styles of feeling, speaking and narrating which prevailed at the time of the sacred writer, and to the patterns men normally employed at that period in their everyday dealings with one another.” —Dei Verbum 12

The relevance of these principles for the exegesis of the Torah, and the use of cult to enter the culture and context of the human sacred writer, becomes more clear when we recall that Moses—upon God’s revelation—instituted both the design of the temple (the Tent of Meeting, or Tabernacle) and the priesthood that would regulate the daily lives of the Israelite community. Once God revealed himself on Mount Sinai, and Moses instituted that pattern in the Tabernacle and in the priesthood, all previous narratives received a final form and were purified of all previous misconceptions. The Tabernacle itself gave a purified cosmology and understanding of creation, while the furnishings inside the temple and the Levitical priesthood established a sacramental worldview and expectation of a future Messiah.

If Moses is to be the substantial author of the written Torah, he most certainly did not first write Genesis and then go to Egypt to begin the Exodus and then communicate the Book of Exodus. The Exodus experience was communicated first, and its language and idioms give cultural context and clues to a proper explanation of Genesis (which was communicated finally after the Exodus). AB/Wikipedia. Moses, by Michelangelo / Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

If Moses is to be the substantial author of the written Torah, he most certainly did not first write Genesis and then go to Egypt to begin the Exodus and then communicate the Book of Exodus. The Exodus experience was communicated first, and its language and idioms give cultural context and clues to a proper explanation of Genesis (which was communicated finally after the Exodus). AB/Wikipedia. Moses, by Michelangelo / Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Most important to all of these considerations, since Moses would not have delivered a Genesis narrative in its final form before the events of Exodus took place at Sinai (with the institution of the Tabernacle and priesthood), then we should watch for how the liturgical and cultic events of the Exodus at Sinai gave penultimate context to the Genesis narrative.

Sinai to Genesis

Prior Israelite traditions of Creation and Eden could not have received a final canonical form before Moses experienced the Exodus along with all of Israel. If Moses is to be the substantial author of the written Torah, he most certainly did not first write Genesis and then go to Egypt to begin the Exodus and then communicate the Book of Exodus. The Exodus experience was communicated first, and its language and idioms give cultural context and clues to a proper exegesis of Genesis (which was communicated finally after the Exodus).

The book of Genesis, apart from the Exodus, would never have been written as we have it today had not the Exodus of Moses been successful. It was the Exodus that preserved Israel from being re-absorbed into other cultures and gave final form to Genesis. Everything depends on the success and traditions of the Exodus (including Leviticus and Numbers) in order for there to be a people even to receive the written Law and Scriptures which we celebrate today—and ultimately, in order for there to be the Book of Genesis we have today.

Indeed, before Moses, there were prior written and oral traditions about gardens of the gods and accounts of man’s beginnings, long before the Israelites and even circulating popularly amongst the Israelites in Egypt who had their own traditions. Umberto Cassuto, the renowned professor and chair of Biblical studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, mentions such sagas and poetry in his eight lectures on the Documentary Hypothesis and in formulating his theory of sources:

“It is no conjecture. . . that a whole world of traditions was known to the Israelites in olden times. . . . From all this treasure, the Torah selected those traditions that appeared suited to its aims, and then proceeded to purify and refine them, to arrange and integrate them, to recast their style and phrasing, and generally to give them a new aspect of its own design, until they were welded into a unified whole.”

The focus of this essay is that whatever those accounts may have included or however they may have served as a material with which Moses and his lawful successors worked, the final canonical form to those narratives was established by the events and revelations of God himself at Mount Sinai, particularly beginning in Exodus 19. They were faithfully continued in the shared and public reality of liturgy as the tradition.

Mount Sinai necessarily served as the interpretative key to whatever should be preserved from prior traditions and whatever should be discarded. It “recast the style and phrasing” of previous legendary material and imprinted its form on what became Genesis. Thus, there is necessarily an interplay of finalization of form in those prior traditions—which eventually helped form the Book of Genesis and which preceded the Exodus—gave some preliminary shape to the Book of Exodus. However, simultaneously, the Exodus event gives rise to what became the final form imposed on Genesis, especially upon the accounts of creation and the Garden of Eden.

Stated as clearly as possible: Exodus recast the style and phrasing of what became Genesis.

Cult and Creation

Since any Israelite receiving Moses’ accounts of creation would already be celebrating the liturgies established in Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, then an Israelite would read Genesis through that existing daily context of worship, Tabernacle, and culture—a culture that was imbued already with the Exodus as the lens through which it understood God and the Land it was to inherit. This is why Exodus actually gives a final form to Eden and Genesis.

Joseph Ratzinger is clear that the “giving of the ceremonial law [Tabernacle and worship] in the book of Exodus. . . is constructed in close parallel to the account of creation. Seven times it says, ‘Moses did as the Lord had commanded him,’ words that suggest that the seven-day work on the tabernacle replicates the seven-day work on creation.” In this passage, Ratzinger prepares the reader to recall an ancient understanding: the building of a temple is a microcosm of God’s creation, so the “account of the construction of the tabernacle ends with a kind of vision of the Sabbath.”

Immediately after connecting the seven-part sequence of Moses building the Tabernacle to the seven-day work of creation and how they explain one another, Joseph Ratzinger implicitly bequeaths a similar principle of exegesis to the one this essay seeks to develop: “Creation looks toward the covenant, but the covenant completes creation.” Likewise, pre-Mosaic traditions of Eden look toward the Exodus, but the Exodus completes Genesis. In a book on liturgy, Ratzinger is expressing implicitly how the covenant of Mount Sinai and the Tabernacle give the final form to understanding correctly the meaning of the days of creation, especially the Sabbath. Liturgy establishes the context for the written Torah.

How would an Israelite during the time of the wandering in Numbers and through the time of Solomon’s Temple hear or read an account of a cherubim guarding the way to Eden? After all, the doors to the entrance of the inner sanctuary of Solomon’s Temple were covered with “carvings of cherubim, palm trees, and open flowers” (1 Kings 6:32) and immediately connected the Israelite’s mind with Eden. AB/WikiArt. The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Paradise (c.1867), by Alexandre Cabanel / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Ratzinger clearly states that the Exodus explanations of the Sabbath finish contextualization of the seventh day of creation. Central to understanding Moses’ substantial authorship of the Torah is understanding with Ratzinger that the “essential work of Moses was the construction of the tabernacle and the ordering of worship, which was also the very heart of the order of law and moral instruction.” This “essential work” is minimally what this essay views to be the substantial authorship of Moses: establishing the worship and cult that gives context to anything written in the Torah.

*Looking Foward: The Exodus of Moses.

**Originally Published on adoremus.org and republished with permission.