In recent years, we’ve experienced a movement to reimagine the “ideal” human body—especially the ideal female body. The “Real Beauty” ad campaign launched by the Dove Soap brand, for example, created a sensation when it debuted in 2004. It featured women of all ages, shapes, and colors laughing together under the heading: “Real Women, Real Beauty.”

Since then, cultural institutions from Sports Illustrated to Miss USA to the fashion world have sought to diversify the standards that they, too, hold up as “beautiful.” Even Barbie dolls now come in a wide range of body types and hues!

Efforts to diversify the “ideal” male physique have likewise been underway—though to less fanfare. By the early 2010s, influence from YouTube (Justin Bieber) and Asian culture had made skinniness and androgyny all the rage. In 2017, the fashion and magazine worlds started using “plus-size” male models. Meanwhile, the global cultural exchange, made possible by the internet, continues to redefine what (for a season) will be considered acceptable and attractive in terms of skin color and physique.

To an extent, our current obsession with body “ideals” is testimony to our historically outsized wealth and leisure. We have time to debate the shapes of dolls—and we have children who own dozens of them! We have a booming fashion industry that can “package” bodies in myriad different ways, hiding flaws and changing body shapes completely. And we have a cosmetic surgery industry capable of utterly transforming one’s natural appearance.

"barbie, portrait" by Sandra Gabriel / via unsplash

"barbie, portrait" by Sandra Gabriel / via unsplash

The Link Between Appearance and Authentic Self

Our outsized wealth, however, only explains the magnitude and range of our body obsession. It doesn’t explain why we have the obsession in the first place.

Why do we think external appearance is so existentially, even mystically important? Why do we link visual expression so closely to personal identity? Why do we (at least, some of us) go to extreme lengths to make sure external appearance aligns exactly with a very specific idea of self? And why do we feel existentially threatened (at least, sometimes) when others don’t seem to “read” our external appearance in a way that matches our preferred idea of who we are?

It seems that—in spite of our well-intentioned efforts to celebrate many different physical “ideals”—we are caught in an ever-escalating, yet impossible, quest for physical perfection. Maybe it’s not a monolithic perfection anymore. (Women don’t feel, any longer, that they have to look like Malibu Barbie.) But it’s a kind of perfection nevertheless: a “perfect” match between the internal and external selves.

There seem to be as many “ideals of perfection” as there are people in the world, and we all seem to be striving to find the one that is ours. In pursuit of this, we dye our hair, get piercings and tattoos, wear corsets or stilettos, and sometimes go to lengths surgical and self-mutilating.

Perfect Renaissance Bodies?

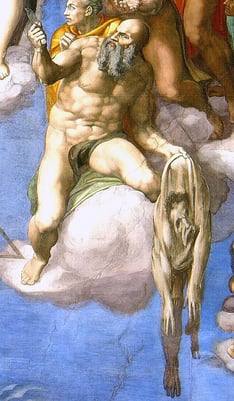

If we reflect on our visual history, it’s easy to blame figures like Michelangelo Buonarotti for our present body obsession. Michelangelo, that quintessential Renaissance artist, made classic images like the Sistine Chapel Creation of Adam and Florence’s David statue—images that celebrate a perfectly chiseled version of masculinity (both literally and figuratively!).

Michelangelo’s older colleague Botticelli, meanwhile, did the same for women (consider his Birth of Venus). It’s reasonable to think that people like Michelangelo and Botticelli engaged in Renaissance-era “body shaming”—holding up one ideal of perfection while diminishing everything else. They (it seems) set the standards we’ve been worshipping, critiquing, or supplementing ever since.

Michelangelo, Public domain / via Wikimedia Commons

Michelangelo, Public domain / via Wikimedia Commons

Surprisingly, however, such a view of these Renaissance masters is a modern projection. In fact, Michelangelo and Botticelli were much more indifferent toward fleeting appearances than we are today! That’s because, to them, personal identity was not lodged in the mortal body. Rather, the true self—the soul—transcended the body and ennobled it.

The buff, beautiful figures of Michelangelo do seem uniformly “perfect” and powerful—but not because Michelangelo thought living people were “supposed to” look that way. Rather, Michelangelo gave his figures their particular stamp to symbolically express a “God’s eye” point of view. Michelangelo’s Sistine figures look impossible because they are impossible. They are mortals symbolically adorned with heavenly glory and the aura of divine destiny.

The Real Source of Identity

For Michelangelo, all humans were brothers and sisters—“genetically” similar children of God. Furthermore, all humans contained a seed of divine purpose and superhuman life. In his Sistine Chapel frescoes (and his Florentine David), Michelangelo used generalized, massive, rather superhuman bodies to indicate these spiritual truths. His splendidly distorted figures suggest that we are more than our social status, our careers, and our family names. Scrubbed of social particulars like uniforms or elaborate hairstyles, Michelangelo’s grave and graceful nudes hint at the awesome mystery of our still-hidden, heavenly selves.

Our twenty-first century, however, sees things in exactly the opposite way. As a culture, we no longer believe that personal identity is determined by the gaze of God, to be fully realized only in heaven. Instead, we believe the “self” is a fragile thing that must be invented by the individual and then constantly affirmed by the “gaze” of society.

Under such a paradigm, self-discovery and self-maintenance are arduous, perilous tasks. Slights and misunderstandings can result in existential crises, destabilizing fragile identities and throwing whole, internal worlds into disarray. If our sense of self comes from looking in the mirror or from looking in the eyes of those around us, it’s no wonder that we’re always lurching and changing and repackaging! We have nothing eternal and stable to orient our lives and “see” us aright.

Michelangelo by Michelangelo

Michelangelo Buonarotti had a sense of humor about his own appearance. He wasn’t anything like the buff figures in his frescoes—and he knew it. His only painted self-portrait can be found in the Sistine Chapel’s Last Judgment scene: on the sagging “skin suit” of St. Bartholomew—a martyr who was flayed to death! In the sacred pictures of the Renaissance, saints often hold symbols of their martyrdom. Here, a transfigured and heavenly St. Bartholomew holds up his poor, wounded, earthly hide, sagging from lack of a skeleton. And its face bears the face of the artist!

The Creation of Adam (cropped), by Michelangelo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Creation of Adam (cropped), by Michelangelo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This visual joke expresses Michelangelo’s healthy, sixteenth-century approach to body image. It can be summed up like this: None of us are perfect here and now. In fact, we might be rather undistinguished or odd. (The prophet Isaiah even said of Jesus Christ: “He had no beauty or majesty to attract us to him.”) But one day we will all be glorious, and we will all be connected. Our shared identities as children of God will shine majestically as our bodies and souls are united in holiness.

Thus, right now, our bodies might indeed be like the “dead flesh” in Bartholomew’s hand, but later we will be like that saint resurrected, resplendent at the feet of Christ. And we have this consolation: that even now, our souls can shine through our “dead flesh” and give us a beauty that transcends social station, health, and age.

Identity in the Gaze of God

Many Christian saints, thinkers, and religious leaders have stressed the importance of finding our identity in the gaze of God. In a 2013 homily, Pope Francis dwelt on Jesus’ gaze, asserting that His eyes alone “give us dignity” and recognize “the embers of God’s image” in us. Pope Benedict XVI often affirmed the healing power of the “eyes of Christ.”

When we experience the gaze of God, we forget about external appearances, and we dismiss the social pressures that formerly shaped our fragile, self-made “identities.” Instead, like Michelangelo at his best, we rest with joy in our true natures as ravishing, beloved children of God.